Staged hunts (venationes)

usually took place in the morning, as an introduction and complement to the gladiators’ combats, that started in the afternoon.

Livy, the great historian of Rome, dates the first hunts to the year 568 AUC (ab Urbe Condita, that means from the foundation of the city, i.e. 185 BC), with the games offered by M. Fulvius Nobilior after the second Punic War against the Carthaginians. In that case they showed african elephants and ostrichs, booty of war.

Livy also tells us that it was a Carthaginian use to expose fugitive slaves to the wild beasts; apparently this foreign custom was warmly welcomed in Rome, and hunts were so popular that the Senate in 170 b.C. forbade the importation of the Africanae (beasts) to Italy.

In the year 660 a.U.C. (219 b.C) Sulla gave a show of loose lions in the forum; in 695 the Romans saw for the first time an hippopotamus and five crocodiles brought by Scaurus from the provinces of Lybia, and in 698 Pompey outdid all of them, at least for a while, having 500 lions killed.

Later on these records were beaten by Caesar and by other emperors, but these shows were enormously popular, since in those times for the Roman people it was the only chance to see exotic wild animals, with the additional pleasure of seeing them being chased and killed. Last, but not least, the meat was offered to the public after the show in what we can imagine as a colossal barbecue. In many cases there was also a show similar to the modern circus, in which the animals performed tricks and games. The public loved these shows that became a staple of the day at the arena.

In the last times of the Republic hunts had become a show in its own right, taking place in the afternoon and sometimes lasting for days. All sorts of wild beasts – elephants, bears, bulls, lions, tigers – were captured all over the Empire, transported to the different locations and kept there until the day of the show. The number of animals slaughtered is appalling: historians tell us of thousands of beasts killed in one day, when the Colosseum was inaugurated.

At the beginning hunts were produced by an editor independently of the gladiatorial games, but after Augustan times they were produced together and became part of one show. Praetores, aediles and quaestores were the magistrates charged with the duty of organizing the hunts, by imposing taxes on the provinces so that the citizens could enjoy its games. Hunts had a religious side, too. They were dedicated to the goddess of the hunt Diana, or to Jupiter, in his different aspects of Latialis, Stygius or Infernalis. Hunts could be ordinary (held on fixed days in the year) or extraordinary (random). Ordinary ones were the birthday of the Caesars and anniversaries of glorious victories. An extraordinary hunt could be called in occasion such as the crowning of a new Emperor, their weddings, the promotion to consul, the dedication of a public building, pro salute Caesaris (to the health of Caesar), wars, victories, triumph and funerals.

Sometimes the hunts took place elsewhere, in the Forum and in the Circus, where a suitable space could be found. Some authors also draw a distinction between the great spectacular hunts and the morning hunts that became routine and took place in the Colosseum before the gladiator combat.

At first, the animals were chained, but after Sulla’s times (about 100 BC) they were freed and special defences had to be built for the safety of the audience. In the Colosseum the wall around the arena, the podium, was 13 feet tall, smooth and provided with top rollers that prevented the beasts from climbing on top. Moreover, a system of nets all around the podium (according to Colagrossi the nets were inside the arena, at about 2,5 metres from the podium) provided an additional safety measure.

The venatores (who were slaves, criminals, or under contract, and who were considered even viler than gladiators) received a special training in the ludi like the gladiators. In Rome there was the ludus matutinus, whose name seems to come from the fact that hunts took place in the morning. They also were divided into categories according to the role performed in the show: archers, bullfighters etc..

Venatores did not risk their lives like gladiators, nevertheless they ran the risk of being tossed in the air by a bull, or being mauled to pieces by a lion, and some fights gave very few chances. Proof of this is seen in Nero’s time, when the final feat required of a gladiator who asked for freedom was to kill an elephant in single combat.

The animals were exposed to the public the day before their death in the arena. In Rome this happened at the vivarium near Porta Prenestina. The beasts were not allowed to enter the doors of the arena, therefore they were restricted in cages under the arena, lifted by pulleys into cubicles placed all around the podium. If the beasts refused to enter the arena, some attendants (magistri) drove them out with blazing straws. If attacked by the beasts, these attendants, who are not to be confused with the hunters (venatores), could find safety inside little boxes placed against the wall of the podium.

The common feature of all venationes was that there were animals in it; they weren’t necessarily killed, and could also perform other roles: Caesar, for instance, produced a giraffe for the first time in Rome, to the astonishment of the citizens, and Augustus displayed all kinds of exotic and strange animals sent for this purpose by the governors of the provinces. Nevertheless, the usual hunt saw beasts matched one against the other, or against men. Scholars draw a line here, and distinguish between two very different forms of hunts: the venatio in which men provided with weapons fought the wild beasts, and another “show” in which men condemned to death were thrown to the beasts without any defence. Venationes usually ended with the show of animals trained to perform tricks, like in today’s circuses. To keep these animals, and also all the beasts that were condemned to find death in the arena, it was therefore necessary to organize a kind of a zoo. It was called vivarium, and at least three locations in Rome and outside it have been identified as probable sites of such a zoo.

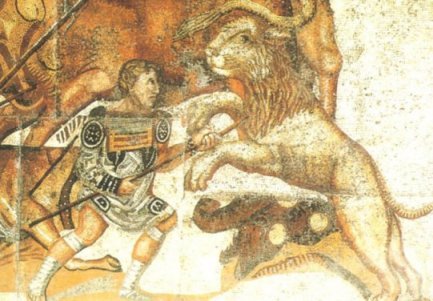

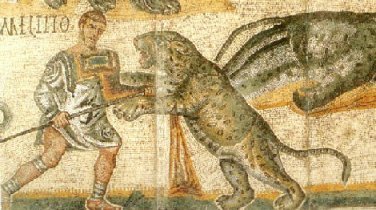

The whole system – from the capture of the beasts in the outskirts of the Empire, to their transport and keeping – assumed the size of an industry, given the scores of animals necessary to produce the shows. In particular, hunts became extremely popular in Africa, where in mosaics we can still find the pictures of famous killer beasts, that were given names such as Omicida and Crudelis.

Most of the matches were classic: a lion against a tiger, or maybe against a bull or a bear. Sometimes the match was very unequal: hounds, or lions were loosed against deers, in which case the outcome was predictable. To break the monotony the Romans resorted to strange combination of animals: hippopotamuses, hyenas, seals and all kinds of felines. We have records of fights of a bear against a python, lion against crocodile, seal against bear and so on. Bears came from Caledonia (Scotland) and Pannonia (Hungary), lions and panthers from Africa, tigers from Persia. Sometimes the animals were chained together, which prevented them from manoeuvring.

The majority of the combats, however, staged the beasts against specially trained men (venatores) armed with a spear. The venatores were protected by leather bands on their arms and legs, and sometimes they wore iron plates on their chests or even a suit of armour (in which case they only had a sword as offensive weapon).

Fighting techniques were many: some venatores were armed as above described, some others were almost naked, with intermediate types of hunters, also including some who fought with their bare hands or with special devices e.g. the cochlea, that was something similar to our revolving doors; behind it the venator could dodge the attack of the beast. Sometimes men rode one of the animals which was matched against the other.

In bullfights, like in modern corridas, bulls were goaded by succursores till they became enraged: the taurarii, the actual fighters, fought the bull on foot, with a pike or a lance. Other bullfights involved skills similar to those depicted in the famous Cretans pictures or contemporary rodeos: unarmed men on horseback raced the bull to wear it down, and then jumped on the bull in order to throw it down by twisting its neck. In other occasions there was a comical element introduced into the combat, the venator appearing in the role of an acrobat, or of a clown. Tame animals would perform numbers: tigers would let themselves be kissed; lions would catch hares and bring them back unharmed, elephants would do tricks like dancing or walking the rope.

Venationes usually ended with the show of tamed animals trained by mansuetarii to perform tricks, like in today’s circuses. To keep these animals, and also all the beasts that were condemned to find death in the arena, it was therefore necessary to organize menageries and parks.

The hunts were extremely popular, since hunting had become the sport of the rich, and it was a proof of courage for the professionals involved. Some venatores became so famous that we can still read their names on some mosaics or graffiti. Will the fame of contemporary soccer heroes survive the centuries ?