The modern architectural study

of the Colosseum started with Carlo Fontana, who, around 1720, made a survey of the amphitheatre and studied its geometric proportions. Most of the ground floor of the building was by now almost submerged by earth and debris accumulated over the centuries, and the arches were used as a deposit for manure.

In 1796 Napoleon I invaded Italy, defeated the papal troops and occupied Ancona and Loreto. Pius VI pleaded for peace, which was granted at Tolentino on February 19, 1797, but on December 28 of that year, Brigadier-General Mathurin-Léonard Duphot, who had gone to Rome with Joseph Bonaparte as part of the French embassy, was killed in a riot so there was a new pretext for the invasion. General Berthier marched to Rome, entered it unopposed on February 13, 1798, and, proclaiming a Roman Republic, demanded that the Pope renounce his temporal authority.

On February 17, 1798 (29 pluviôse An VI) General Berthier ordered the Pope to leave Rome within three days, but he refused and was taken prisoner. On February 20 he was escorted from the Vatican to Siena, and thence to the Certosa near Florence. Then, via Parma, Piacenza, Turin and Grenoble he reached the citadel of Valence, capital town of Drôme in Southern France, where he died six weeks after his arrival, on August 29 1799. He had reigned longer than any Pope in historical times.

The Roman Republic proved short-lived, as Neapolitan troops restored the Papal States in October 1799. The French Revolutionary Army invaded the Papal States again in 1808, and the French occupation lasted until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

According to the French project, the Colosseum was to become part of a huge archaeological park comprising the whole centre of Rome. The monument was in a bad state, because coach drivers used it as a night shelter, and it had been for a long time a storehouse of manure destined to a nearby gunpowder factory. These abuses damaged the stone and blocked the corridors. The 1703 earthquake had caused another partial collapse of the building, and the stones were used to build the Porto di Ripetta.

Carlo Fea, Commissioner to the Antiquities, visited the monument and in 1804 wrote a memorandum suggesting the structure to be cleaned by taking away the manure, unearthing the entrance steps and freeing the entire first corridor. He pointed out the importance of consolidating the north east corner, which was in danger of collapse. One week after the presentation of the report there was an order from the Quirinale to clear the Colosseum from abuses.

In 1805 the excavations started, carried out by architects Camporesi, Palazzi and Stern, with the help of Carlo Lucangeli, an artist of wood modeling who needed an exact survey of the monument for his reproduction. The three architects presented further plans for the consolidation of the Colosseum, proposing the building of a buttress to stop the lateral movement of the outer wall. The idea was criticised in name of the picturesque and romantic qualities of the ruin, which would be spoiled by the monstrous buttress.

A counter proposal was presented to the Pope by one Domenico Schiavoni, possibly a master mason who had been assisted by an architect. He suggested turning the endangered part itself into a buttress by demolishing the upper parts along an oblique line and by walling in some arches. This intervention – they said – would produce the appearance of a natural ruin.

The three architects were appalled and strongly objected to this proposal: “The shamelessness to present a similar sacrilegious project to the Sovereign was unknown even at the time of the Vandals and Goths; although then it was true that plans of this kind were carried out, at least the devastations were done without asking for the approval and financing of the government”.

They promised that with half the sum of money requested by Schiavone they would secure the Colosseum “As we hope, in its integrity and declaring to everybody how highly the fine arts are valued today and how dear the precious relics of Roman grandeur are to us. These are objects that all the people of the world come to admire and envy us for. It is of course clear that if that kind of vandalistic operation had been approved, it would have been better to leave the endangered parts in their natural ruined state – instead of taking steps to secure them. In such case, we would at least have been accused of lacking the means, but never of being destroyers and barbarians”.

In 1806, after another earthquake had done further damage to the outer ring, the project was finally approved. A wooden shoring had prevented the collapse of the outer wall, but when the works started it was found that that wall was in worse conditions than expected, so it was deemed necessary to build a cross wall to link the buttress, the outer wall and the inner structure of the monument. Also, were excavated the niches around the podium, parts of the podium, the entrance of the so-called passage of Commodus, part of the drain that runs around the amphitheatre and part of the canalisation system of the ground floor. The porticoes were finally liberated from the earth, and so were the third corridor and other rooms.

In 1809 and 1810 the works restarted, with the help of forced labour. In 1811 the northern part of the monument and the northern side of the arena were partially excavated by Carlo Fea, but the works had to stop at a depth of 3 metres because of water infiltrations in the arena. From 1811 to 1813 more repairs were made, and the arches were liberated from the walls that had filled them.

In 1814 the authority of the Pope was re-established The temporary administration contracted out to Luigi Maria Valadier, son of the more famous Giuseppe, a survey of the undergrounds, the arena was then covered again and the stations of the Cross reinstalled.

Under Pius VII (1800-1823) it was deemed necessary to reinforce the remains of the outer ring. An abutment (buttress) of bricks (a.k.a. the “Stern abutment”, from Raffaele Stern, the architect who planned it) was built to support the arches on the NW side, ad was completed around 1820.

Later on, in 1826, the following Pope Leo XII had the other, more photographed abutment built by the architect Giuseppe Valadier. In 1828 Antonio Nibby managed to empty all the surface drains, and in 1830 Luis Joseph Duc made the first complete survey of the monument with modern means.

From the 1840s on, more arches were restored and rebuilt on the side of the Celian Hill (these arches are easily recognized as they are made of brick) by architect, restorer and archeologist and Gaspare Salvi (not to be confused with Nicola Salvi, the author of the Trevi Fountain).

Then in 1852 Luigi Canina repaired the second ring of corridors and rebuilt part of the Maenianum summum in ligneis, where he wanted to reproduce a section of the colonnade by using modern elements. On this occasion the tie rods that cross the facade and anchor it to the masonry behind were installed.

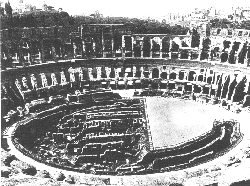

In 1870 Rome became the capital of the new Italian State, but the works to finally free the arena restarted only in 1874. In the end this time half of the arena was liberated from debris and the excavations reached the bottom, where a type of paving made from brick, known as opus spicatum was found.

These excavations were very rewarding, as capitols, pieces of columns, inscriptions and debris dating back to the end of the V and the beginning of the VI century were found in the arena. It was on this occasion that the stations of the cross in the arena were finally removed, notwithstanding fierce opposition of the Catholic Church, that considered the act a profanation.

Later on, more excavations were carried out on the northern side, and in the end the whole facade on that side was liberated from the debris accumulated over the centuries. Also the streets around were redesigned (Via Claudia and Via degli Annibaldi). The works to install drains and gas pipes led to more discoveries: the paved area around the amphitheatre on the N side, boundary stones and a road.

In 1895 the valley was again unearthed and 89 burial places, dating from Diocletian to Theodoric times (IV-VI century) were discovered in and around the amphitheatre. More restoration works were carried out by the Italian State in 1901-2, but the arena remained half full of earth for many years.

During the Fascist regime the Colosseum was used for propaganda gatherings, since Mussolini wanted to connect the past Imperial Roman glories with the birth of the new fascist Empire.Unfortunately the then Sovrintendente Terenzio lamented that capitols and columns had been damaged during those rallies.

The Colosseum was then adapted so as to accommodate mass rallies: some corridor floors were covered with asphalt, connection stairs were made that modified the original structure, and a small section of the cavea with seats was inaccurately reconstructed in 1933 (there were no seats there, but wide steps where the Senators placed their personal chairs). See the picture on the right.

In the 30s the landscape around the monument changed radically: the Velia, the hill that joined the Exquiline and Fagutale hills, was razed to build the road of the imperial parades, so that the Duce could see the Colosseum from his balcony in Palazzo Venezia. Away with the Meta Sudans, that blocked the passage under the Arch of Constantine.

On the other side of the Colosseum via di San Gregorio was widened, and an underground railway was built in the 40s, mercilessly cutting the foundations of the amphitheatre on the western side and damaging the outflow of the waters, so that nowadays the undergrounds are often flooded in case of heavy rain. On the other hand, we now have this famous backdrop….

In 1938-40 the excavations carried out by Luigi Cozzo arrived at the very bottom, bringing to light the underground of the arena. Cozzo also demolished 567 cubic metres of underground structures that had been added to the original construction during the millennia and 1059 cubic metres of unstable masonry. These demolitions have been criticised on the grounds that Cozzo acted with haste and without a serious study of what was being dismantled.

When the western side of the underground was reached in 1939, a heap of columns from the upper porch and structures of the cavea were found. The square around was completely asphalted, so that cars could even go inside the corridors and under the Arch of Constantine.

During the World War II the Colosseum became a bomb shelter and the Wermacht even made there a weapon deposit (still today weapons are found during the excavations!) Constant small repairs have been made since WW2, and a major restoration of some arches on the NW side was started in 1978.

After the war the Colosseum became the most famous Rome backdrop for tourists, but at the same time with the increase of traffic it was practically a roundabout, probably the largest in Europe! In the 70s car traffic was finally banned between the Colosseum and the Palatine, though many Romans would like to see the whole central area, including the Fora, free from traffic.

More excavations of the drains gave precious insights into the story of the amphitheatre, and the restoration of the top floor facade allowed archaeologists to study the repairs made after the fire of year 217.

In 1992 a private bank financed restoration works that lasted until 2000, and only a section was restored; its cleanliness dramatically contrasting with the rest of the monument (see that in the picture on the main page). Future works include the rebuilding of the arena in wood, so as to protect the exposed underground structures from the weather. The eastern half of the new arena was completed in 2000, and studies are being carried out on the effect of the new cover on the underground microclimate before covering the other half. In 1997 a very important survey measuring the Colosseum with laser and infrared techniques was carried out. This research has given us some insight on the deformation of the structures and a very precise map of the amphitheatre, and rekindled an old controversy between the archaeologists: is the Colosseum elliptic or ovoidal?

Recent restoration

On 2011 Diego Della Valle, CEO of Tod’s Group, started supporting financially the restoration of the Colosseum, blackened by pollution and rocked by vibrations from the nearby subway line.

The first part of the intervention plan was completed with the restoration of the northern and southern prospectus (approximately 13,300 square meters), and the replacement of the actual locking system of arches with new gates.

The second phase of the project, which began in December 2018, has focused on the Colosseum’s hypogea, the portion of the amphitheatre which lies below the arena and that in ancient times was invisible to the spectators. The restoration saw the involvement of more than 80 people, including archaeologists, restorers, architects, engineers, surveyors and construction workers.

At the end of the works, a 160 metre long walkway was installed in the Colosseum, opening up to visitors an area of the monument that had never been accessible before.

Main source for this page: Il Colosseo – AA. VV. – Care of Ada Gabucci, Electa, Milan 1999